DOMINIQUE VAN DE WALLE|JANUARY 11, 2016

In Western economies, widows were historically among the poorest and most vulnerable individuals until the introduction of pension schemes and widow benefits in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. One might expect a similar situation in developing countries with underdeveloped safety net and insurance mechanisms, as well as high levels of gender inequality in rights, human development, and access to assets and employment. Yet, despite the likely relevance of widowhood in the lives of African women, surprisingly little is known about the well-being of Africa’s widows.

This is partly because poverty and vulnerability are typically measured with the household as the basic unit of observation. Potentially disadvantaged individuals such as remarried widows, young or elderly current widows, and their children are then largely hidden from view in standard data sources. In a background study to the latest World Bank Group Africa poverty report, Poverty in a Rising Africa, we mined Africa’s Demographic and Health Surveys to dig deeper into these issues. The findings are telling.

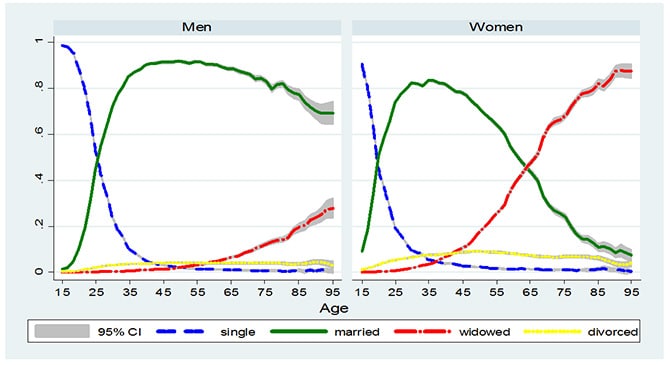

To begin, the experience of African widowhood is remarkably gendered (see Figure). African men spend far more of their lives married than African women. From their early thirties to their early eighties, more than 80% of all men are married. In contrast, the share of married women peaks at around 30—and lasts a much shorter period, dropping below 80% just after age 40. The drop is then precipitous and mirrored by a steady rise in the share of widows. By age 65, there are as many widows as there are married women; by age 80, 80% of women are living in widowhbood.

The experience of widowhood is gendered

This reflects several factors: the far higher remarriage rates among men following widowhood or divorce, the greater average life expectancy of women, and, in places, the ravages of HIV and conflict. As a result, one in 10 African women 15 and older are widows. And these women are much more likely to head their own households; 72% are heads of the family.

What’s more, we typically think of widows as elderly. But in Africa, a fair share of these women are also quite young. Across the region, 3% of all women aged 15-49 are widows at any point in time. Including the many young widows who remarry, more than 5% of ever-widowed women are under the age of 49.

But are Africa’s widows disproportionately disadvantaged, as was historically the case for widows in Western economies? After all, the shock of widowhood entails a loss of economic means that are conditional on marriage, including access to productive assets (such as land), as well as the loss of protection and status previously derived from a husband. And this leaves aside the still-common (in places) imposition of extended periods of seclusion, degrading rituals and accusations of having caused the death to which, it goes without saying, widowers are not subjected to.

A few recent studies get around the data issues by using individual measures of welfare such as nutritional status or innovative measures of individualized consumption together with disaggregation by marital status. The following insights emerge:

In Mali, widows are found to disproportionately head the poorest households. They also have lower levels of nutritional status than women of other marital statuses controlling for age. This disadvantage persists through remarriage and spills over to their children’s health and education outcomes

In Nigeria, worse nutritional status for widows can be linked to inheritance practices and cultural attitudes and norms towards widows associated with certain ethnic and religious groups

In Senegal, and elsewhere, some protection for widows may be provided by the opportunity to remarry. The evidence indicates that among widows in Senegal it is the worst off who remarry, while those who can afford not to do so often don’t. Among those who remarry, half marry a relative of their deceased husband. In a context where women’s rights and access to property remain linked to men, remarriage can be a life saver. There is also evidence that Senegalese women whose husbands already have children from other marriages, and hence ‘rivals’ for his inheritance, reduce birth spacing and increase the number of pregnancies to potentially dangerous levels in their desperation to have a son as insurance against widowhood.

We need to better understand the consequences of losing a husband, and what role policy should, and could, play in protecting women, who are oftentimes young. Through changes in inheritance laws and their enforcement, cash transfer schemes, and preferential access to housing, training, employment and schooling for their children, social policies can potentially help compensate for the misfortune stemming from the shock of widowhood.