By TOLULOPE AJIBOYE

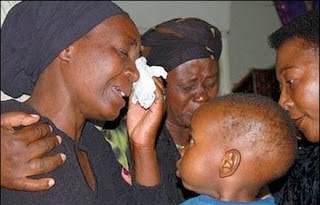

Widows in many African cultures are subjected to dehumanizing cultural and ritual practices passed off as mourning rites—practices, it must be noted, that widowers are rarely ever put through.

In Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Malawi, widows must undertake a requisite cleansing. It basically entails a widow having unprotected sex with her husband’s brother or other relatives, or with a professional village cleanser to remove the impurities that have been ascribed to her. It’s done before the widow is taken into marriage by the brother or the other relative of her deceased husband. In Kenyan tradition, it isn’t just after their husband’s death that they’re expected to go through this, cleansing is also expected preceding specific agricultural activities, building homes or making repairs to them, funerals, and some other significant cultural and social events. It’s intended to provide protection for the widow, her children, and the whole village. Failure to perform this rite leads to ostracism. Widow cleansing has been strongly linked to the spread of HIV/AIDs in these countries.

In the South-Eastern part of Nigeria, widows go through a period of confinement—ranging from 8 days to 4 months—beginning when the husband’s death is discovered. In this period, the widow is not allowed to leave her room and her hair is completely shaved. She is expected to sit on the floor and wail at the top of her lungs every morning and is not allowed to take a bath or change her clothes till the body of the deceased is buried.

It’s almost impossible to separate death from witchcraft in most West African cultures. There is a presumption that his wife murdered her husband, especially when the death occurred in middle or young age. In order to prove her innocence, the widow is made to drink the water used in washing the corpse. In some cultural variations, she is also made to sleep beside the corpse for some days. The logic is this: If she dies after doing all this, she is guilty. Refusal to comply is tantamount to a confession of murder, for which she must be punished.

One of the last stages of the Igbo culture’s widowhood rites is called Aja-Ani. It is essentially widow rape. At midnight, some days after her husband’s funeral, the widow is expected to go out escorted by an Aja ani—priest—or Nwa nri—dwarf—to a place where he is supposed to perform a ritual for her. The widow is expected to engage in sexual intercourse with the priest or dwarf. Her consent is immaterial. The community and the dead husband’s family insist on her rape. After this, some of the Umuada±patrilineal sisters—escort her to a stream where she washes before returning home. It is done to sever her links with her dead husband for it is believed that any man who tries to sleep with her before its performance will die.

Economically, these widows are left impoverished. In some of the major Nigerian cultures, widows aren’t allowed to inherit property. They are seen as chattel and part of their husband’s estate. Upon his death, his property is usually forcefully acquired by his family, leaving the widow and children to fend for themselves.

Similarly, in the matrilineal society of the Ashanti in Ghana, the properties of the deceased are inherited by his sisters’ sons or nephews. Among the patrilineal societies of the Anlos and Gonjas in Ghana, male relatives of the deceased inherit his property. The widow can only benefit from it if she has a grown male child, or she marries one of her husband’s brothers. In the Baule society of Cote d’ivoire, the widow must return to her family after the period of mourning, along with her young children. She gets nothing of her husband’s property.

This same principle applies to widows in Kampala, Uganda, and Cameroon. Seeking court redress on inheritance issues is slowly on the rise. But as it is right now, only a handful of people can afford to institute and maintain court actions.

Why don’t the widows out-rightly refuse to partake in these rites? The societies examined above, and indeed most others, are inherently patriarchal and traditionally against the economic independence of women. Most of the women have grown up believing that there’s nothing they can or should do to escape these customs. Some want to but can’t because they do not have the financial resources to uproot their lives—and that of their children if they have any—and leave the community.

Widows across Africa are treated as sub-human. Their fundamental human rights are constantly violated. The mental and physical health effects of these rites on widows are indescribable—but it’s important that we note their social and economic realities. We must observe the impact of these customs in order to define a fight against them moving forward.